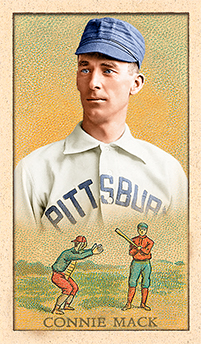

Baseball is a sport built for superlatives and appellations; with every passing season, another member of the sport seems to be bestowed the title of “the Greatest” or a nickname. Yet, there is only one “Grand Old Man of Baseball,” and there will never be another like Irish American Connie Mack nor anyone as deserving of the title.

Connie Mack was born Cornelius McGillicuddy in Brookfield, Massachusetts, on December 22, 1862. His parents were both Irish immigrants, Michael McGillicuddy from Killarney, while Mary (nee McKillop) McGillicuddy was from the Catholic section of Belfast. Connie would never legally change his name of McGillicuddy and used it on all formal documents but would use ‘Mack’ as his last name in all other situations.

Mack’s father was a Civil War Veteran whose health had been destroyed by his service. The family eked out a survival based on a meager disability pension supplemented when the father could work and could find it. Mack left school at age 14 to help support his family. It was remembered that he would always give his mother whatever he earned. Later in life, Mack would always be self-conscious about his lack of formal education.

One advantage of working in the local factories and mills was a lunch hour where Mack would play baseball, which he would follow up with additional playing in the evening when work and chores were done. Standing 6′ 2″, Connie Mack was already the tallest boy in town and quickly earned the name of “Slats” for his height and slim build. In 1879 he was playing for Brookfield’s town team. Only 17, Mack was much younger than his teammates but was the team’s catcher and de facto captain.

In 1886, Mack began a major league career (though the term’ major leagues’ was not coined yet) as a catcher. Sports writer Bill James described Mack’s playing career as “a light-hitting catcher with a reputation as a smart player but didn’t do anything particularly well.” That is both uncharitable and inaccurate. Mack was an expert at “the dark arts” of being a catcher. Instead of positioning himself in front of the backstop like other catchers, Mack was among the pioneers who positioned himself directly behind the home plate. According to a contemporary opponent Wilbert Robinson, “Mack never was mean … [but] if you had any soft spot, Connie would find it. He could do and say things that got more under your skin than the cuss words used by other catchers.” In addition to distracting hitters, Mack also honed skills such as blocking the plate and simulating the sound of a foul tip when the then rules stated that any pitch tipped and caught by the catcher was an out. Mack was also an expert at “tipping bats” (catcher’s interference) to throw off a hitter’s swing.

Mack’s final three seasons were with the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1894 to 1896, where he served as a player/manager and compiled a 149–134 (.527) record. In 1896, he retired as a full-time player to begin the career he became famous for as a manager. After a four-year stint as a manager for the then minor league Milwaukee Brewers, Mack became manager, treasurer, and part-owner of the new American League’s Philadelphia Athletics. Mack guided the A’s to triumph, leading them to capture nine pennants and reach eight World Series, ultimately securing five victories..

Mack revolutionized the position of baseball manager. He was praised for his intelligent and innovative management, which earned him the nickname “the Tall Tactician.” He was among the first managers to strategically reposition his fielders during the game, frequently guiding outfielders by waving his rolled-up scorecard from the dugout.. He valued intelligence and “baseball smarts,” trading away Shoeless Joe Jackson despite his proven worth as a hitter because of his poor attitude and unintelligent play. Mack’s strength was finding the best players, teaching them well, and letting them play. In an age when baseball was known for its flamboyant rowdy individuals, Mack developed the need for what we would now call ‘team culture.’ The Times wrote of Mack, “He was a new type of manager,” The Times observed. “The old-time leaders ruled by force, often thrashing players who disobeyed orders on the field or broke club rules off the field. One of the kindest and most soft-spoken of men, he always insisted that he could get better results by kindness. He never humiliated a player by public criticism. No one ever heard him scold a man in the most trying times of his many pennant fights.”

However, what set Connie Mack apart was that he was known as a consummate gentleman, a trait he attributed to his Irish mother. Going against the baseball manager stereotype, he rarely drank and didn’t smoke or curse. Time magazine once said, “Mr. Mack, as his players called him, remained a gentleman. Rumor had it that the harshest expletive was a mild ‘goodness gracious.‘” Ironically, Connie Mack did have a temper, which is why he adopted the practice of wearing his signature business suits rather than the team uniform, as was the habit of other managers. This meant that he did not need to go to the locker room with his players after a game to change, and by the time the team cooled emerged, he would have cooled down.

Mack also had a wry sense of humor. When fellow manager John McGraw described the A’s as a “white elephant that would never make money,” Mack had a picture of an elephant added to the uniform, turning the insult into a badge of pride. The use of the white elephant logo is still used by today’s Oakland A’s continues.

However, when McGraw was proved at least partially correct, the team struggled financially, resulting in Mack having to sell off players to keep the team viable, earning him an unjust reputation as ‘miserly.’ On the contrary, Mack supported a large extended family and demonstrated kindness to players who were down on their luck, including paying for one former player’s funeral. More than once, a fellow Irish American would claim to be a relative; Mack knew they weren’t while at the same time leaving some free tickets for them at the box office.

Connie Mack would manage the Athletics for fifty years, compiling a record of 3,582–3,814 (.484) when he retired at 87.When Mack retired as a manager at 87, old age and the changing nature of the game had caught up with him, and it can be argued that he diluted his Baseball accomplishments by hanging on too long. Still, nothing can diminish his influence on the game of baseball or the qualities as a gentleman instilled in him growing up in an Irish American household.

“Humanity is the keystone that holds nations and men together,” Mack once said. “When that collapses, the whole structure crumbles. This is as true of baseball teams as any other pursuit in life.“

Connie Mack