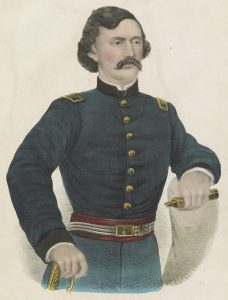

On 22 September 1864, an Irish-American Civil War officer became a national hero after losing a battle! His name was James A. Mulligan. James was born in Utica, New York, in 1829, to Irish immigrant parents. After his father’s passing, he and his mother moved to Chicago where, at age 27, James was a popular Irish-American lawyer and Democratic politician. At a time when the Irish population of Illinois was more than 87,000, he commanded the respect and allegiance of Chicago’s large Irish community. He joined a local National Guard unit called the Chicago Shield Guards and was appointed Captain.

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Mulligan organized one of the first Irish regiments of the Civil War – the 23rd Illinois Infantry Regiment which included the Chicago Shield Guards. Raising a regiment of volunteers required initiative and political savvy. Mulligan published a call for volunteers among the Irish community and when enough were recruited to form a regiment, they selected officers and established a training camp. Then a petition was filed with Governor Yates for acceptance into state service and it was granted. A brigade consists of three regiments or more led by a brigadier general, but it should be noted that smaller Irish units on both sides of the conflict would often use the term ‘Irish Brigade’ to link themselves with the renowned Irish Brigades of the 18th century. Such was the case with the 23rd Illinois Infantry regiment which became known locally as Mulligan’s Irish Brigade and later, nationally, as the Irish Brigade of the West.

Mulligan’s Irish Brigade got off to a rough start. In 1861, they built and lived in Fort Mulligan near Petersburg for several months when they were ordered by General John C. Fremont to immediately move to the isolated Union outpost in Lexington, Missouri. They would be joined by a Union Cavalry Regiment along the way. Ordered to travel light in order to reach Lexington before a Confederate force, moving north, could get there, they set out for Lexington on 30 August with just forty rounds of ammunition and three days’ worth of food for each man. Mulligan was assured that supplies and reinforcements would soon follow. They marched for ten days to reach the small city, searching for the Cavalry regiment to no avail. Arriving in Lexington, they found a small cavalry force with few supplies. All told, there were now less than 3,000 Union troops in the town. Col. Mulligan took command and began fortifying the Masonic College in the city center as his base.

On 11 September, Confederate Major General Sterling Price arrived at 9 AM with a force of 18,000 rebels and the siege was on. In fierce fighting, Mulligan’s men were able to drive them back. This small victory did not solve the Union supply problem however, and by Sunday, 15 September, the troops had virtually run out of food. The Irish, now cut off from help, celebrated Sunday Mass with their chaplain under the eyes of the 18,000 Confederates who now surrounded them. After Mass, the soldiers found that the wells they had used for water had run dry. They became so desperately thirsty that they drank the bloodied water that the wounded had been bathed in. Mulligan later remembered the men with ‘parched lips cracking, their tongues swollen, and the blood running down their chins’ as they bit into their powder cartridges to load and fire their guns.

By Sept. 20, after three-days of intense fighting against Mulligan’s courageous defense, Price’s troops used hemp bales soaked in river water as mobile walls to slowly advance. They gradually moved closer and closer to the lines of the severely outnumbered Irish Brigade. A Confederate officer recounted the scene: ‘Two or three men would get behind a bale, roll it awhile, then stop and shoot. A line would be advanced in this way.’ General Price wrote that Mulligan’s troops ‘made many daring attempts to drive us back’, but ultimately they were overwhelmed and battling through the city streets. With his men almost out of ammunition and many having had neither food nor drink for days, Mulligan polled the six officers of his command and four voted to capitulate. Arrangements were made under a flag of truce and the Union garrison conceded defeat on the College grounds to save the lives of their starving men. Gen. Price’s troops captured the Irish, five large guns, 3,000 small arms and 750 horses and more than $900,000 in cash and gold from the Lexington bank. Confederate casualties were listed at 25 killed and 72 wounded. The Union force suffered 159 killed and wounded. General Price was so impressed by Mulligan’s courageous stand and conduct during and after the battle that he offered him his personal horse and buggy and a safe escort back to the Union lines; the 23rd Illinois was exchanged for Confederate prisoners in November.

Amid fiery accusations, General Fremont later claimed that ‘All possible efforts were made to relieve Colonel Mulligan’ but many accused him of abandoning the Irish Brigade. Blair’s newspaper wrote that Mulligan had assumed that ‘with forty thousand Federal troops within a few days march, he would be saved’ by Fremont, but that ‘the heroic officer calculated too largely on the cooperation of Fremont.’ Mulligan and his Irish regiment won national fame for their courageous defense at Lexington, in spite of their unavoidable surrender.

After their exchange, Mulligan’s regiment earned a distinguished and heroic record on many battlefields. They went on to fight in West Virginia, the Shenandoah Valley and served in pursuit of General Lee’s army to Appomattox, developing a reputation as a solid regiment. In 1862, Mulligan held command of Camp Douglas near Chicago for five months. In 1863, it was back to war as defending Greenland Gap in Hardy County, members of his Irish Brigade held a farmhouse for twelve hours against superior Confederate forces until it was set afire and the roof caved in on them. In 1864, Mulligan and his Brigade distinguished themselves during battles in and around Leetown, Virginia, including the Second Valley Campaign, where they faced Confederate General Jubal Early. Being vastly outnumbered by the Confederates once again, Mulligan’s Irish were ordered to hold and delay the rebels as long as possible to cover the retreat of other Union forces. He bought valuable time allowing Union forces to successfully concentrate their forces in the valley.

On July 24, 1864, while engaged with Confederate forces in the Second Battle of Kernstown in the Shenandoah Valley, Mulligan was mortally wounded. When his men attempted to carry him from the field of battle he saw that the emerald green banner of the 23rd Illinois was about to be captured and he shouted to his men ‘Lay me down and save the flag!’ They did as he commanded and he was captured; three days later, he died from his wounds. The legacy of Mulligan’s Irish Brigade is not that well known today, but it should be. Two of the Brigade’s men: John Creed and Patrick Highland, both Tipperary men, were awarded the Medal of Honor and future U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes even met the popular Irish-American hero on the battlefield. Mulligan’s body was returned home. Calvary Cemetery was newly established at the time of Mulligan’s death and he was given a place of honor immediately inside the main gate. To this day, Mulligan’s monument is always planted with flowers.

On July 24, 1864, while engaged with Confederate forces in the Second Battle of Kernstown in the Shenandoah Valley, Mulligan was mortally wounded. When his men attempted to carry him from the field of battle he saw that the emerald green banner of the 23rd Illinois was about to be captured and he shouted to his men ‘Lay me down and save the flag!’ They did as he commanded and he was captured; three days later, he died from his wounds. The legacy of Mulligan’s Irish Brigade is not that well known today, but it should be. Two of the Brigade’s men: John Creed and Patrick Highland, both Tipperary men, were awarded the Medal of Honor and future U.S. President Rutherford B. Hayes even met the popular Irish-American hero on the battlefield. Mulligan’s body was returned home. Calvary Cemetery was newly established at the time of Mulligan’s death and he was given a place of honor immediately inside the main gate. To this day, Mulligan’s monument is always planted with flowers.