When someone wants to quickly set an atmosphere of “Irishness,” whether it is a major motion picture or a local Irish restaurant, they invariably use the same element: music. Music is an essential element of Celtic life; the harper, piper, and the fiddler hold a place of honor and esteem. Wherever the Irish have traveled, they have taken their music with them as one of their prize possessions, and the sound of Irish music can be heard in Dublin, Denver, and Durban. Irish music is a highly personal art form; it is an aural tradition passed on from generation to generation through playing and listening. It is one of our culture’s most identifiable and enduring elements. Yet, it was nearly lost if not for the tenacity and dedication of one man: Chief Francis O’Neill.

O’Neill was born in the town of Tralibane, West Cork, on August 28, 1848, one of ten children. He was fortunate enough that his childhood was spared the horrors of the Great Hunger, but he would witness the scars that this tragedy left upon the land and its people and the pattern of massive emigration it set in motion. The O’Neill’s appeared to have weathered the Great Hunger and subsequently prospered by the standards of rural Ireland of the time, allowing young Francis an opportunity at a good education. The O’Neill home was constantly filled with music, O’Neill’s maternal grandfather was respected as one of the last of the Gaelic clan chieftains, and he would follow the ancient custom of extending hospitality to itinerant musicians. O’Neill’s mother naturally absorbed a great collection of the tunes and songs of Munster and, through her singing, passed them on to young O’Neill, creating what he would in later life describe as a “madness” for music. Francis taught himself the flute and soon became an accomplished player.

O’Neill’s education and quick mind seemed to destine him to be a teacher or for the priesthood, but the quiet life of a scholar was not appealing to the young man. At the age of 16, he ran away to sea, circling the world at least twice and surviving a shipwreck in the South Pacific and a subsequent “Robinson Caruso” existence. O’Neill left the sea and married a young Irish woman he had met on one of his voyages. He tried ranching in Montana and teaching in Missouri before finally settling in Chicago.

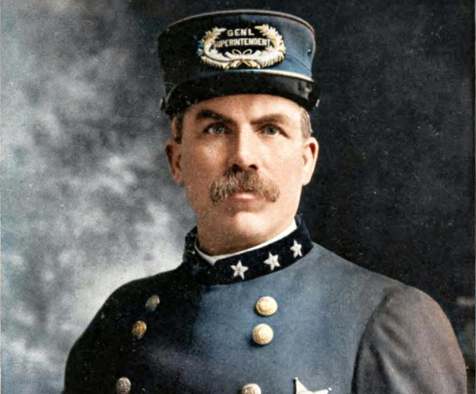

In the aftermath of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, the city of Chicago earned a reputation for lawlessness and corruption. O’Neill was sworn in as a policeman in 1873 and was shot a few months later while apprehending a notorious gangster. The bullet was too close to the spine to be removed, and O’Neill carried it for the rest of his life. Achieving top marks on every police exam he took, he soon worked his way up through the ranks, eventually obtaining its highest rank as Superintendent, also known as “Chief.” Renowned for his honesty, he once locked up a powerful alderman and personally redesigned the Chicago Police Badge so that Id numbers were more visible and Officers could be held more accountable. O’Neill was so respected that even in an age where patronage was rife, he maintained his appointment over two different administrations.

However, music remained O’Neill’s passion. He soon found in the rich Irish immigrant community of Chicago that he had within a few blocks radius access to musicians from across the breadth of Ireland and traditional tunes which were known only locally back home. However, O’Neill saw in this byproduct of the diaspora not only an opportunity but a crisis: as the Irish spread across the world, the aural tradition of Irish music was removed from the close confines of Ireland, and its protective incubator was in peril. O’Neill actively sought out Irish musicians and began collecting tunes. Following in his grandfather’s footsteps and giving a new connotation to his official title, “Chief,” O’Neill would often sponsor Irish musicians in need of employment for jobs on the Chicago Police Department. A running joke at the time was, “What do you call an Irish Musician in Chicago? Officer. What do you call a great Irish Musician in Chicago? Sergeant.“

O’Neill had one limitation in his tune collecting; like many Irish Musicians, he learned by ear and had a tremendous ability to retain tunes in his head, but he could not read nor write music. Fortunately, one of his officers James O’Neill (no relation), was not only a respected fiddler but could read and write music. O’Neill would act as a human tape recorder going about the city, mentally capturing tunes he heard and then playing them back for James O’Neill to set down on paper. What was unique in Francis O’Neill’s endeavor was that this was not preserving the music of kings and heroes of a bygone age; this was creating a permanent record of the music of the ordinary people of Ireland, the music of the parlor and the ceili. When Thomas Edison’s phonograph was displayed at the 1893 World’s Fair, O’Neill was one of his first buyers. Thanks to Chief O’Neill, we can hear some of the legendary Irish Musicians of the age.

O’Neill eventually published eight books of traditional Irish music; his “The Music of Ireland” is considered a definitive reference. According to the Music Librarian of Notre Dame, “Without (Francis O’Neill), the music would have died.” Thanks to Irish American Francis O’Neill, the rich legacy of Irish music was preserved for generations.

It is a reminder of how fragile our history and culture are and the duty of all of us to “Keep the tradition alive.”

Neil F. Cosgrove