John Phillip Holland was born on February 24, 1841 in small coastal town of Liscannor, County Clare. His mother was a native Irish speaker and young John himself would not learn English until he attended school. Holland’s father was a coastal patrolman for the British Coastguard Service and instilled in the young Holland a love of the sea. With aspirations to go to sea, young Holland walked 5-1/2 miles each way to attend the Christian Brothers secondary school in Ennistymon because they offered a course in navigation. However Holland’s dreams of maritime life were soon dashed by frail health which would plague him throughout his life and poor eyesight.

The family moved to Limerick, where Holland became a student of Brother Bernard O’Brien, a distinguished science teacher and excellent engineer who was a tremendous influence on him. With his father’s death, young Holland began a career as a teacher, and then decided to take his initial vows as a Christian Brother himself. It soon became apparent that young Brother Holland was an inveterate inventor, at one point building a mechanical duck that fascinated his students.

Holland’s health soon intervened in his aspirations to be a Christian Brother. Falling ill, Holland was sent to an Aunt for treatment and to recuperate. While recovering, Holland was taken by accounts of the ongoing Civil War in America and was particularly fascinated by reports of a revolution in Naval warfare: the battle between the ironclads USS Monitor and the CSS Virginia (Merrimack). Holland realized that the age of wooden ships was gone forever and that ironclads were the future. As a child who had experienced the dark side of British rule during the Great Hunger, Holland was concerned that England’s industrial might positioned her to dominate the new technology. Holland wondered “how [other peoples of the world] would protect themselves against those designs.” The course of Holland’s life was set.

Holland returned briefly to the Christian Brothers, but before he could make his final vows illness struck him again causing him to withdraw from the order. Holland decided to follow his mother and brothers who had immigrated to America. Arriving in 1873, Holland took a lay teaching position at St. Joseph’s school Paterson and brought with him plans to counter England’s naval ambitions: a submarine.

Holland initially approached the U.S. Navy to sponsor development of his submarine, but his design was dismissed as impractical. However, Holland’s brother Michael soon found a sponsor for Holland’s work: Clan na Gael, the American branch of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, or Fenians who saw in it a weapon to fight for Ireland’s freedom. After a successful demonstration, the Fenians funded development of a full size submarine that would later be dubbed the ”Fenian Ram”. Holland’s submarine had many of the features that became fundamental to submarine design: it was driven by a combustion engine on the surface, but used battery power when submerged, it was fitted with both ballast and compressed air tanks. In an initial trial, the submarine made 3-1/2 knots on the surface and was able to stay submerged for over an hour and successfully return to the surface.

However, there was one challenge that Holland had not counted on: the classic “Irish split”. Internal fighting within the Fenians and allegations of inappropriate use of the “skirmish fund” resulted in cancellation of funding for Holland’s submarine development. A faction of the Fenians stole the “Fenian Ram” and another prototype. The prototype sank in transit while subsequent attempts by inexperienced crews to operate the “Fenian Ram” resulted in it being impounded as a menace to navigation.

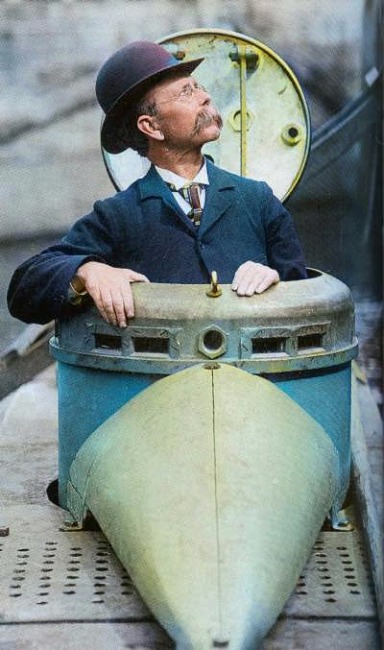

Submarines however were finally gaining the attention of the U.S. Navy. Holland competed for and won a contract to develop a submarine to be named the USS Plunger for the Navy. However, Holland soon realized that the Navy’s shifting design requirements were dooming the project to failure. On his own Holland began developing his own design, the Holland VI. When sea trials came, the USS Plunger proved to be the disaster that Holland had predicted. Holland then demonstrated the Holland VI which in trials exceeded the Navy’s requirements. The Holland VI was commissioned into the U.S. Navy on April 11, 1900 as the USS Holland, the U.S. Navy’s first modern submarine and an order for an additional six more was placed.

It would be nice if the story could conclude on this triumph as a happy ending, but it cannot. Holland’s vision always exceeded his meager pocketbook and he was near poverty. To continue his work Holland formed a partnership with Isaac L. Rice, a businessman who controlled the manufacture of the storage batteries that were integral to Holland’s design. Holland and Rice formed a new company, fittingly called Electric Boat, which is still in operation today as the leader in submarine design. Holland soon found that his partner began isolating him, forcing him into less and less significant roles within his own company while others took credit for Holland’s ideas as they now rapidly evolved with proper financial backing. Holland left Electric Boat to form his own company, only to be dragged through the courts by Electric Boat who claimed not only ownership of Holland’s patents but even Holland’s own name as applied to submarines. While Holland eventually won in court, the damage had been done, potential investors had been scared off. Holland, broken and bitter, was forced into retirement. John Phillip Holland died at his home in Patterson on August 12, 1914 just as World War I was breaking out in Europe, a war in which Holland’s vision of the submarine would be proven with devastating effectiveness.

The genius of Irish Immigrant John Phillip Holland deserves a kinder fate. Holland’s discoveries and his over twenty patents are still protecting our national security today in the shield that is the Navy’s submarine fleet.

Neil F. Cosgrove ©