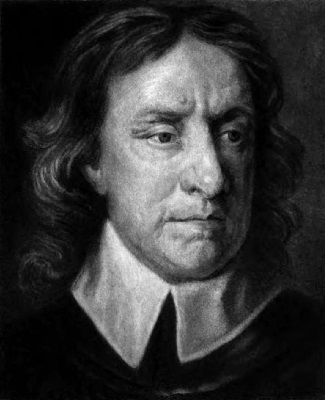

On August 14th, Cromwell landed at Dublin with 10,000 foot-soldiers, 4,000 cavalry and enough artillery to crush all resistance by the Irish and those who had supported the former King. On 3 September he began his campaign at Drogheda. For eight days, 2,800 men defended the town against the onslaught until a breech in the walls allowed Cromwell’s army to storm in and cut down the defenders to a man. What followed became the trademark of his victories across Ireland. Under Cromwell’s order of ‘no quarter’, the army indiscriminately slaughtered the defenders as well as the defenseless civilian population; for five days men, women and children were hunted and butchered. On 2 October, Cromwell appointed a national day of thanksgiving in celebration of the dreadful slaughter at Drogheda of which he wrote, The enemy were about 3,000 strong in the town. I believe we have put to the sword the whole number . . . In this very place (Saint Peter’s Church) a thousand of them were put to the sword, fleeing thither for safety. Hugh Peters, Cromwell’s chaplain, gave the total loss of life as 3,552, of whom about 2,800 were soldiers, meaning that between 700–800 were civilians. A few survivors were sent into servitude to English settlers in Barbados.

On 11 October, after reducing the northern strongholds in quick succession, Cromwell swept south to Wexford where, as Lingard states in his History of England, Wexford was abandoned to the mercy of the assailants. The tragedy recently enacted at Drogheda was renewed. No distinction was made between the defenseless inhabitants and the armed soldiers, nor could the shrieks and prayers of the 300 females who had gathered round the great cross in the market-place, preserve them from the swords. Cromwell reduced the garrisons of Arklow, Inniscorthy and Ross on his way to Wexford. After Wexford, he attacked Waterford and laid waste to the cities of Cork. He then rested at Youghal awaiting fresh supplies from England.

In January, Cromwell took the field again and reduced Fethard, Cashel, and Carrick. At Clonmel, he was met by Hugh O’Neill, nephew of Owen Roe, and a small garrison of 1,500 men. They put up the last major resistance to the Puritan army. By May, Cromwell left for England after the bloodiest campaign ever seen by the Irish. He left his son Henry and General Ireton in command of the English army. For the next two years, scattered pockets of resistance were systematically wiped out.

In 1652, after three years of slaughter, the last of the Irish Clansmen accepted Cromwell’s terms of surrender. In August, the Cromwellian Act of Settlement was passed stating that all Irish who couldn’t prove that they had supported Cromwell’s Army were to forfeit all properties and land and remove themselves west to the poorest and most barren part of Ireland or face execution. To Hell or To Connaught – a phrase that conjures up bitter feelings to this day – was the choice given. This amounted to the seizure of a fortune in personal property and more than 11 million acres of the best land in Ireland. English speculators, who had advanced monies to raise the army for service in Ireland, were rewarded with confiscated land. Unable to pay its soldiers in cash, all debts were paid in Irish land; thus was Ireland made to pay for her own conquest.

The Irish were given six months to move out and some took to the hills living as outlaws raiding the English settlements. More than 34,000 went abroad to chance their fortunes in the Irish Brigades of foreign armies. Those who owned no property or land, were left to form a workforce of laborers for their new English masters with the stipulation that they were not permitted to live in the towns. At this point in Irish history we can say that those descendants of Norman conquerors finally became as Irish as the Irish themselves since they were now dispossessed just as their ancestors had dispossessed the native Irish. They were now in the same social, economic, and political position as the native Irish had been. And the native Irish moved a step lower on the socio-economic ladder, as a caste of itinerant peasant laborers, forced to live in the woods and fields away from the towns in their own land.

As a result of Cromwell’s slaughter, swarms of widows and orphans; starving, unemployable survivors of both sexes wandered everywhere. Some of their descendants still travel the roads of Ireland today, but in 1652 the English solved the problem by selling them to commercial agents to ship to Barbados, Montserrat, St. Kitts and Virginia to be sold into service to English colonists. In 1633, Jesuit Father Andrew White on the ship, Dove, from England to Maryland in Lord Baltimore’s expedition, wrote that on the way over they put in at Monserrat where they found a colony of Irishmen who had been banished from Virginia on account of professing the Catholic Faith (see Old Catholic Maryland, p. 14). The deportation of the Irish to the plantations was so profitable a business that enterprising merchants were soon kidnaping Irish men, women and children to expand the trade. Records show that from 1651 to 1654, 6,400 exiles were sold to English colonies in Barbados and America. The following year, 2,000 more boys and girls were shipped and it was estimated that in the year 1660, 10,000 Irish had been distributed thus among the different English colonies in America (see American Catholic Quarterly Review, IX, 37). Of the total number thus shipped out of Ireland, estimates vary between 60,000 and 100,000 [Lingard, History of England], X (Dolman ed., 1849), p 366.

Many who ended up in theses colonies endured a hell on earth. Women and elderly men were sold first; then the children were dragged kicking and screaming to the auction platform where they were stripped and examined. Rich planters and their wives desired young boys as pages and young girls as servants; however, homosexuals and pedophiles frequented the auctions as well, buying children whose fate would be years of debauchery until they became too old for such purposes and were sold to the brothels of Bridgetown in Barbados for the pleasure of visiting sailors. Worst of all were those children who were part of a cruel plan to develop a ‘master slave’. Irish children were considered trainable, but too susceptible to sunburn to make good workers in the tropical sun; male slaves from Africa were considered strongest, but less trainable. To breed a perfect slave, Irish girls as young as 11 and 12-years old, who had never even seen a black man before, were sent to ‘breeding sheds’ where they were continually impregnated by Mandingo men until they too, by their early twenties, were considered ‘worn out’ and sold to the brothels. When a volcano destroyed part of Montserrat in 1995, files saved from the island’s library documented lineage records of those matings, kept in the same way as pedigrees are kept for dogs and thoroughbred horses.

Of all the many English plantations of Ireland, Cromwell’s, which began 370 years ago this month, was the worst. But, the greatest of all plantations was the plantation of an unforgiving hatred in the hearts of the Irish, for the Irish never permitted themselves to forget it. To this day, the curse of Cromwell on ye remains one of the harshest curses an Irishman can utter.