As an Army chaplain, Fr. Francis L. Sampson saw combat in two wars and earned the nickname of “the Parachuting Padre.” His actions during the D-Day campaign would be adapted as part of two major motion pictures, though his actions would be attributed to others.

Fr. Sampson was born in Cherokee, Iowa, the descendant of Immigrants from County Cork. Fr. Sampson graduated from Notre Dame before entering St. Paul’s Seminary in Minnesota. He served briefly as a parish priest. When the U.S. entered the war, Fr. Sampson sought and was granted permission to join the Chaplain Corps of the U.S. Army. After completing training, he volunteered for the Airborne, though he later admitted he did not know that he would be required to jump or the harsh rigors of the training. He was assigned to the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, of the 101st Airborne Division, as the regimental chaplain.

On June 5th, Fr. Sampson joined his men as they boarded the C-47 aircraft. He was carrying a prodigious weight, not only the religious articles of a Catholic priest, but the supplies of a medic. As the plane began to taxi, Fr. Sampson looked at the young men with charcoal-covered faces and wondered how many would survive the night. He and the men bowed their heads, and he led them in prayer.

As they approached the French coast, the aircraft was buffeted by antiaircraft fire. One man was severely wounded by flak piercing the plane but insisted he was going to jump with his comrades. The red light came on, and the paratroopers moved to the door of the aircraft. The green light came on, and the command “GO” was shouted. Father Sampson exited the door and into the plane’s engines’ prop blast as he plummeted until his parachute deployed. Tracers from enemy machine guns surrounded him. “It will always remain a mystery to me how any of us lived,” he later wrote.

Fr. Sampson landed in a flooded canal, the heavy weight of his equipment dragging him under. Fumbling for his knife, he was able to cut himself free from his pack, yet still might have drowned had it not been for a divine gust of wind filling his still attached parachute, which pulled him into shallow water. Freeing himself from his parachute harness, Fr. Sampson then dove “five or six times” to retrieve his Mass kit and the holy oils for the last rites, items he would sadly need all too soon. This scene was recorded accurately in Cornelius Ryan’s book “The Longest Day,” but when the film was produced, the incident was inexplicably changed to a fictitious British Army Chaplain.

Fr. Sampson made his way to an aid station at Basse Addeville which was currently under German counterattack. Seeing how grievously wounded some of the men were, Fr. Sampson volunteered to find a surgeon, at times wading through chest-high frigid water and enemy fire. He Successfully returned with a surgeon and desperately need supplies, only to find upon his return that the unit had orders to abandon the Basse Addeville position leaving those unable to move.

Fr. Sampson volunteered along with a medic to stay behind with the wounded men unable to move. He was well aware of the risk he was taking; neither side was taking many prisoners in the current fluid situation, and the Germans would view the wounded as a liability.

The Germans realized the position was abandoned the next morning. Elite German paratroopers entered the village and quickly seized Fr. Sampson. Despite showing the crosses on his collar and red cross armband, two grim young paratroopers marched Fr. Sampson outside, away from the building. They placed him against a hedgerow, stepped back, and pulled back the bolts on their submachine guns. Fr. Sampson later confessed that facing imminent death in nervousness, he began reciting “Bless us O Lord and these Thy gifts,” Grace, rather than The Act of Contrition.

No pair of knees shook more than my own, nor any heart ever beat faster in times of danger

Fr. Francis Sampson

The Priest’s heart must have stopped when he heard a shot and then realized it was not from his would-be executioners but a German NCO running down the road. Shoving the impromptu firing squad out of the way, the NCO saluted, made a formal bow to the Priest, and then produced a Sacred Heart medallion from under his uniform. The Catholic NCO took the Priest to an English-speaking German office, who, after a few questions, released the Priest as a noncombatant, leaving the wounded, including some of his own men, to his care.

For his bravery, Fr. Sampson would be award the Distinguish Service Cross and recommended for the Medal of Honor (see note below). Fr. Sampson would later humbly dismiss any praise of his heroics, saying, “no pair of knees shook more than my own, nor any heart ever beat faster in times of danger.”

Finally returning to the rear lines, Fr. Sampson was called upon to perform another act which formed the basis of an award-winning film. Headquarters had just received orders concerning a young paratrooper, Frederick Niland of the 101st. The young man was one of four Irish American Niland brothers serving in WW II; three were at Normandy, the other serving with the Air Corps in the Pacific. Frederick Niland had just found out that the two brothers with him in Normandy had been killed; he did not know that just before they took off from England, word had come that his brother’s aircraft in the Pacific had been shot down and was presumed dead. Fr. Sampson was given orders to find the young man and tell him he was ordered home; his family had sacrificed enough. It was this story that formed the basis of the movie “Saving Private Ryan.”

“You can take that up with General Eisenhower or the president, but you’re going home.”

Fr. Francis Sampson

Fr. Sampson’s journey to find the last of the Niland brothers was not as dramatic as that of Tom Hank’s, but it had its own challenges. When Fr. Sampson found Niland with his unit and told him that he was to return with him for transport back to the states, Niland refused, saying, “I’m staying here with my boys.” Fr. Sampson would have none of it; “You can take that up with General Eisenhower or the president, but you’re going home.”

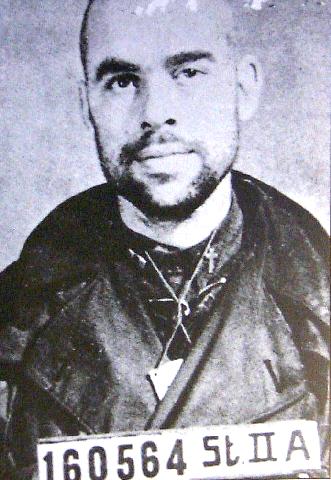

Fr. Sampson would jump again with the 101st in Holland during the Arnhem Campaign and be captured while tending to the wounded during the Battle of the Bulge. Father Sampson refused transfer to an Officers POW Camp and, at his request, was confined with the enlisted men in the brutal Stalag II-A in Northern Germany until the end of the war.

Returning briefly to civilian life, Fr. Sampson reenlisted at the request of the Military Ordinariate, Francis Cardinal Spellman. Fr. Sampson parachuted into Korea, near Sunchon, with the 187th Airborne Infantry Regiment and endured some of the Korean War’s heaviest fighting. Fr. Sampson served in Viet Nam and was appointed the Army’s chief of chaplains in 1967, attaining the rank of major general. He would serve as an Army Chaplain for 29 years and then, after his retirement, a further two years tending his military flock as head of the USO.

EndNote: Fr. Sampson was recommended for the Medal of Honor by no less a person than General Dwight Eisenhower, but Army Chief-of-Staff George C. Marshall denied the request without explanation. It is believed that Marshall was implementing an unwritten rule that chaplains were ineligible for the award. Despite Army chaplains subsequently being awarded the Medal of Honor and recent awards of the Medal of Honor to address similar injustices, Fr. Sampson still is not recognized.

THIS IRISH AMERICAN HERITAGE MONTH PROFILE IS PRESENTED BY THE ANCIENT ORDER OF HIBERNIANS (AOH.COM)

#IrishAmericanHeritageMonth

Neil F. Cosgrove ©